In recent months, the antimony market has been thrust into the spotlight due to soaring prices and a critical supply shortage exacerbated by China’s export restrictions. This shift in antimony has raised alarms not only in the industrial and renewable energy sectors but also in national security circles.

Antimony’s pivotal role in the defence industry cannot be understated as it is required in everything from bullets to lasers to night vision goggles. As the world’s largest producer, China holds a dominant position in the antimony market, followed by Russia, a fact that has serious implications for the United States, which remains heavily reliant on Chinese imports of this essential mineral. Amid this crisis, Military Metals (CSE:MILI), a Canadian-listed company, is positioning itself as a key player by acquiring a portfolio of brownfield and advanced exploration antimony assets historically used for military purposes.

Antimony: A strategic material with no substitute

Antimony is a critical material with no known substitutes for key applications with various uses, making it indispensable in industries like defense and electronics. Historically, antimony has been used in the manufacturing of flame retardants and lead-acid batteries. However, it is also a vital component in military equipment, including armor-piercing ammunition, night vision goggles, infrared sensors, and precision optics. Antimony’s metallurgical properties, such as its ability to harden lead and increase the durability of other alloys, make it crucial for various types of ammunition.

As global conflicts like the war in Ukraine and tensions in the Middle East escalate, demand for military equipment that relies on antimony has surged. In 2023, U.S. foreign military sales reached a record $238 billion, driven by the need for weapons and technologies, bolstering antimony demand. With no viable substitutes and an increasing demand for defense applications, securing a steady supply of antimony has become a matter of national security.

China’s dominance in antimony production and exports

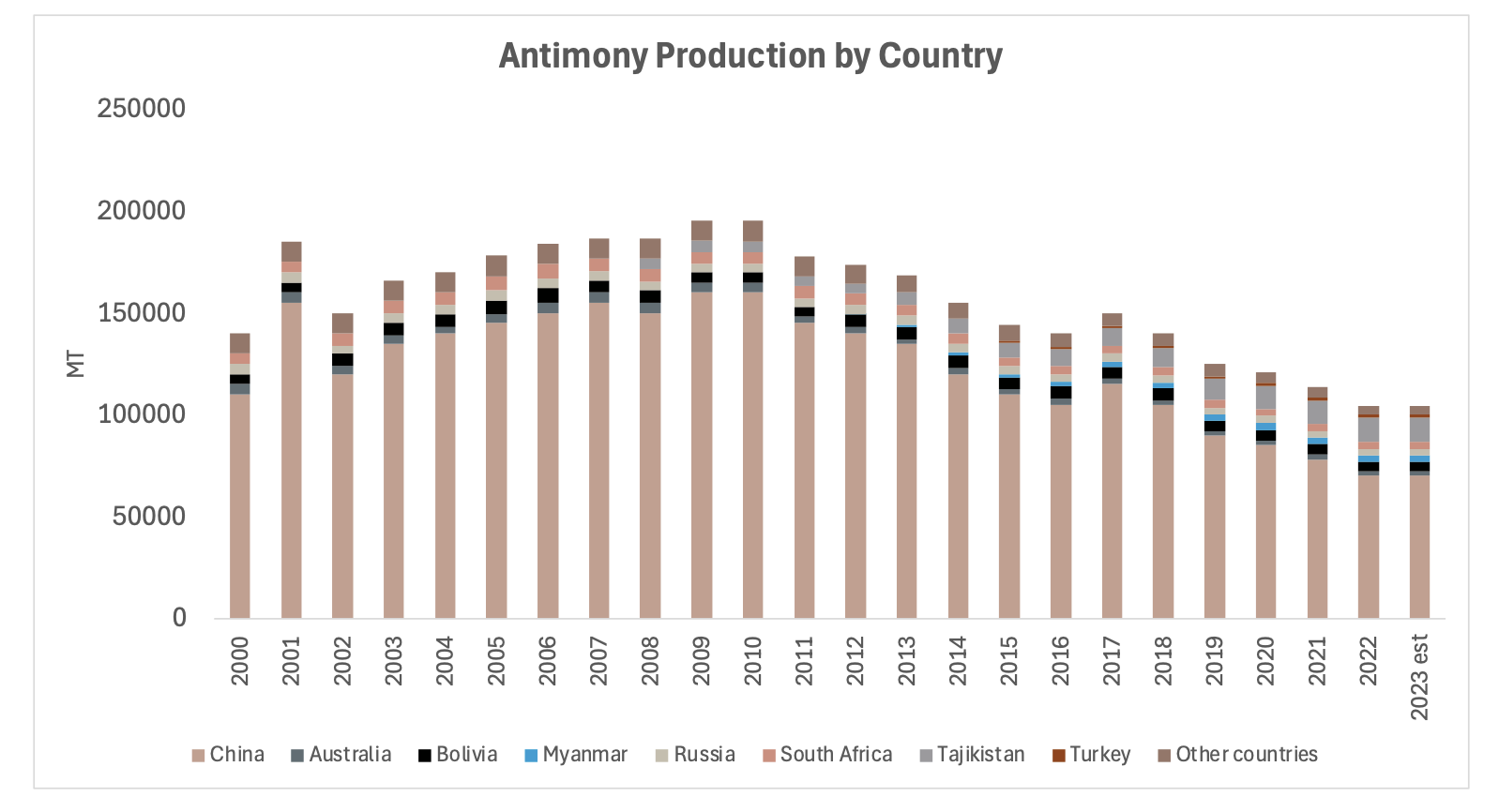

China’s recent decision to restrict antimony exports further underscores the global reliance on its supply. China is the world’s largest producer of antimony, accounting for 48% of global production and 63% of U.S. imports. This dominant market position has given China significant leverage over industries and nations dependent on this critical mineral. The August 2024 announcement of export controls, set to take effect in September, adds antimony to the list of materials like gallium, germanium, and rare earth elements that China has restricted in recent years.

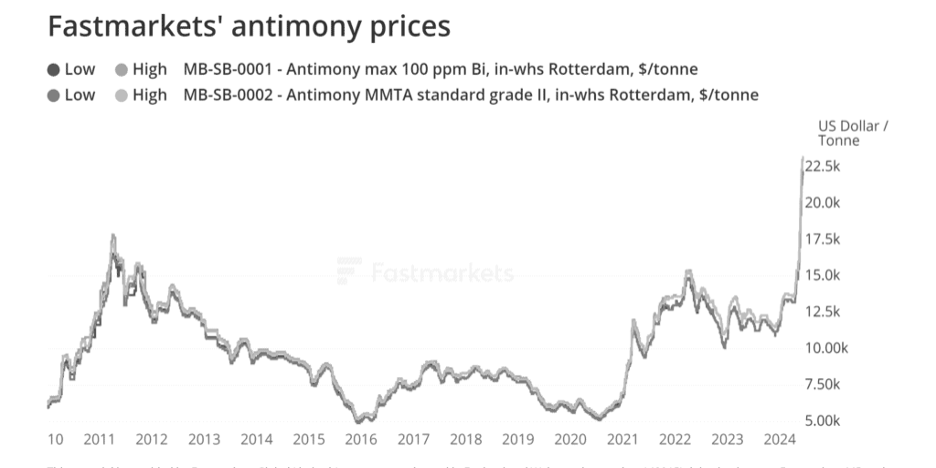

These export restrictions are expected to exacerbate the current supply shortage. Prices have tripled in 2024, hitting record highs of $38,000 per metric ton, with predictions that they could soar as high as $50,000. Furthermore, the largest roaster outside of China in Oman that supplied much of Western antimony trioxide and ingots (20,000Mt of contained antimony) has gone into bankruptcy owing to the limited availability of raw materials.

China’s justification for these export controls is rooted in national security concerns, which are likely tied to the country’s own strategic initiatives, particularly in the defense and renewable energy sectors. For example, the growing demand for antimony in the production of solar panels, which are crucial to China’s green energy ambitions, has shifted more of the country’s antimony supply toward domestic consumption.

Note that the Other Countries refers mainly to Zimbabwe Iran Afghanistan and Pakistan which mainly go to China with minimal volumes from Mexico that is earmarked for the US

The U.S. antimony supply crisis

The U.S. currently faces a precarious situation when it comes to antimony supply. The last domestic antimony mine, located in Idaho, ceased operations in 2001, leaving the U.S. dependent on imports to meet over 80% of its demand. While some antimony is recovered through the recycling of lead-acid batteries, this accounts for only 18% of total consumption. With its reliance on Chinese imports and stockpiles that are inadequate for long-term needs, the U.S. finds itself vulnerable to supply disruptions. Moreover, even if the country could somehow procure a significant stockpile of antimony concentrate, its processing and roasting ability to produce antimony ingots and antimony trioxide, needed for critical applications, is woefully inadequate.

China’s recent export restrictions have heightened this vulnerability. Without sufficient domestic production, the U.S. must look to alternative sources, including countries like Tajikistan, which is the second-largest producer of antimony. However, even Tajikistan’s output is mostly shipped to China for processing, further complicating efforts to secure non-Chinese sources of refined antimony. With limited reserves of its own, the U.S. is struggling to diversify its supply chain in a market where China controls both the production and midstream processing of antimony.

National security implications and defence concerns

The role of antimony in defence technology makes the current shortage even more pressing. The U.S. Department of Defense has recognized the urgency of this supply crisis, offering financial support to projects like Perpetua Resources’ Stibnite mine in Idaho, which aims to resume domestic antimony production. While this project offers a potential solution, production has been postponed several times and is not expected to begin until 2028, leaving the U.S. without a reliable domestic source for several more years. Moreover, Perpetua’s antimony grades are low, averaging less than 0.5% Sb, raising questions about the economic viability of large-scale production. To put into perspective, roasters need a minimum of around 25% antimony concentrate to produce metal and antimony trioxide (though 40-55% is preferred). Currently, there are producing mines in Turkey running at 1-2% feed-grade struggling to increase the concentration to the pre-requisite 25%. Even if Perpetua was able to mine antimony, separate it from the gold, remove the deleterious elements such as arsenic, it is still unclear whether its Antimony would be viable for a roaster.

Gary Evans, co-CEO of the U.S. Antimony Corporation, has highlighted the broader implications of this shortage. With ongoing military engagements and commitments in Ukraine and Israel, the U.S. is rapidly depleting its antimony stockpiles. Current efforts to locate alternative sources of supply are underway, but the ability to replace Chinese imports remains limited. Evans notes that, while some foreign antimony sources are being identified, processing capabilities within the U.S. are underdeveloped. This is a critical issue, as the majority of antimony mined outside China is still sent to China for refining due to the country’s dominance in midstream processing technologies.

The broader impact of China’s export restrictions

The role of antimony in defence technology makes the current shortage even more pressing. The U.S. Department of Defense has recognized the urgency of this supply crisis, offering financial support to projects like Perpetua Resources’ Stibnite mine in Idaho, which aims to resume domestic antimony production. While this project offers a potential solution, production has been postponed several times and is not expected to begin until 2028, leaving the U.S. without a reliable domestic source for several more years. Moreover, Perpetua’s antimony grades are low, averaging less than 0.5% Sb, raising questions about the economic viability of large-scale production. To put into perspective, roasters need a minimum of around 25% antimony concentrate to produce metal and antimony trioxide (though 40-55% is preferred). Currently, there are producing mines in Turkey running at 1-2% feed-grade struggling to increase the concentration to the pre-requisite 25%. Even if Perpetua was able to mine antimony, separate it from the gold, remove the deleterious elements such as arsenic, it is still unclear whether its Antimony would be viable for a roaster.

Gary Evans, co-CEO of the U.S. Antimony Corporation, has highlighted the broader implications of this shortage. With ongoing military engagements and commitments in Ukraine and Israel, the U.S. is rapidly depleting its antimony stockpiles. Current efforts to locate alternative sources of supply are underway, but the ability to replace Chinese imports remains limited. Evans notes that, while some foreign antimony sources are being identified, processing capabilities within the U.S. are underdeveloped. This is a critical issue, as the majority of antimony mined outside China is still sent to China for refining due to the country’s dominance in midstream processing technologies.

Military Metals: A new player in antimony

As global supply chains strain under the pressure of Chinese export restrictions, new companies are stepping into the antimony space. Military Metals (OTCQB: MILIF), a Canadian-listed antimony exploration company, is acquiring a portfolio of brownfield and advanced exploration antimony assets. These assets have historical significance, having been used for military purposes in the past.

For example, their recent acquisition of the West Gore mine, operative during World War I, saw its antimony cargo sunk by a German U-boat while en route to support the war effort in Europe. In Slovakia, Military Metals has acquired former USSR-era antimony mines that were left untouched since the 1990s after serving Soviet military needs. Now part of the European Union, Slovakia’s antimony deposits could prove crucial in diversifying global supply away from China.

During Soviet rule, Slovakia underwent extensive drilling across several deposits. A series of adits were constructed to explore and assess the value of the resources. However, when certain commodities were no longer in demand, many of these adits were sealed. As a result, the adits now included in Military Metal’s antimony portfolio fall into two categories: (1) mined adits, which have been fully extracted, and (2) exploration adits, where resources remain untapped. Many of these adits are still in good condition and can be reopened at low cost, enabling the company to conduct confirmation sampling to verify historical resource estimates. Two notable examples are shown above:

- Trojarova Adit: Located in Pezinok, Western Slovakia, it was estimated in the 1980s and 1990s to contain approximately 60,998,000 tonnes of antimony.

- Vysna Adit: Part of a 10-km concession in Tienesgrund, Eastern Slovakia. This adit was reopened two years ago, and its resources require resampling.

Given the condition of these adits, it is fair to state that Military Metals Corp (CSE: MILI) holds some of the most advanced exploration projects managed by a Western group.

The urgent need for a diversified supply chain

With no domestic production, limited stockpiles, and no substitutes, the U.S. faces a significant challenge in securing a stable supply of antimony. As China tightens its control over this critical mineral, the U.S. must explore alternative sources and invest in domestic production capabilities. Companies like Military Metals (CSE:MILI) are stepping up to fill the gap, but it will take years to bring these projects online. The ongoing supply crisis has made one thing clear: securing a reliable source of antimony is not just an economic imperative—it is a matter of national security. Without significant changes to the global supply chain, the U.S. and its allies will continue to face the risks posed by China’s dominance in the antimony market

_______________________________________________________________________________________

This is a paid for advertorial by the company and written independently by Core Consultants PTY LTD. This is not considered to be investment advice.