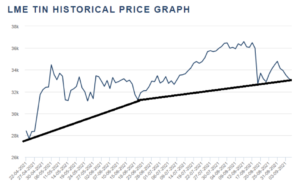

Tin prices are at all-time-highs and rising, and while additional production is inevitable at current levels, there is a distinct lack of new tin mines currently in development. Ongoing supply disruptions and emerging inhibitory factors continue to support the positive price trend, and as it creeps towards $50k/t, it falls to existing cassiterite mines such as those owned by Bushveld Minerals Ltd (LON:BMN), AfriTin Mining Ltd (LON:ATM) and Alphamin Resources Corp (TSXV:AFM) to grow output in the medium term. Of the three companies, only Alphamin Resources has a high enough grade and sufficient resource to impact global tin supply.

Generally, global commodities markets have experienced something of a slump these last six months; but the more industrial metals, particularly those involved in batteries and other electronic products, have continued to increase in value. Over the last year, cobalt is holding above $50k from $33k a year earlier, nickel has increased in value by 20%, and tin has grown by 100%.

What happened?

The covid era brought about extreme demand growth for electronics products at the same time as logistical impediments slowed

the supply of tin. In 2021, electronics manufacturers were reporting sales increases of up to 100% YoY, but mine disruptions related to the pandemic slashed supply by more than 20%. Resultantly, tin inventories in the world’s largest metals exchanges have been depleted to only a few days’ worth of global consumption at the time of writing.

The LME cash price of tin was propelled as high as $36.5k/tonne in 2021, and while it has since settled to around $33k/tonne, the long-term uptrend remains intact. However, we continue to see slower-than-expected output growth in the largest producing countries: China has introduced increasingly stringent environmental regulations, Malaysia announced a moratorium on new exploration licenses in 2019 (shelving a tin project from Australian junior, Elementos), while protests by coastal communities in Indonesia threaten to disrupt the expansion of offshore tin mining by the world’s second-largest producer, PT Timah.

This has been extremely beneficial to existing producers. In particular, those with the lowest operating costs, which are generally African projects, are having a record-breaking year. While Bushveld enjoys a fairly low production cost of around $15,000/tonne, Alphamin’s Mpama North comes in as low as $10,000/tonne; unsurprising for the highest-grade tin deposit in the world, but nonetheless leading to Alphamin’s most profitable period to-date.

What goes up must come down. Right?

A similar series of events happened in the cobalt market between 2016 and 2018: projected demand from increased production of electric vehicle batteries propelled the price from under $20k to almost $100k; however, a key difference was the largely hypothetical demand that drove the cobalt market to extreme highs. The price rise had a distinctive speculative shape and feel, and as new supply came online and demand projections were revised downward, the correction was equally swift and dramatic thanks to its largely psychological support.

From what we can see, the tin market is not following the same speculative pattern. Given the real-world nature of the demand for tin, and the relative scarcity of new tin supply, the approach to similar highs has the potential to be more gentle and sustained. A pullback may certainly expected, but many market participants see strong potential for prices to be sustained above $50k.

Over the long term, demand for tin is likely to consistently rise driven by increased global consumption of electronics, the rise of the internet of things and the green energy revolution, which will of course depend heavily on electronic technology. In the here and now, silicon microprocessor production is a great indicator of tin demand, but this market is also experiencing significant production shortfalls. The shortage of microprocessors has slowed tin consumption since the chips must exist for them to require soldering into final products like personal computers and cars.

But with around $500 billion being committed to new semiconductor production in the next five-to-ten years, we should see a retreat of the silicon shortage and a resumption of full production, allowing automobile makers and electronics manufacturers to resume operations at full pace. For producers like Alphamin with costs in the lowest quartile, the immediate future looks extremely rosy. The real question, however, is where the price will end up once the dust has settled.

Cassiterite is the key

Over the last few years, the supply & demand mechanics of the tin market have kept prices firmly under $20,000/tonne and discouraged investment in fresh supplies. New mine development is encouraged beyond 25k, but prices must be sustained above this level for at least a couple of years for any real progress to be made. It’s no secret that new mining operations can take 10-15 years to bring to fruition, and according to Fitch Solutions, among others, there is a significant shortfall of new sources of cassiterite presently being developed.

Cassiterite, a hard crystalline mineral composed of tin and oxygen, is the only economic form of tin currently known, with pure cassiterite yielding around 80% tin metal. Supply gaps may be filled in the short-term by expansion of existing projects, but this brings its own issues, such as declining grades (and thus increasingly costly extraction).

Of the current cassiterite projects in the works, the ones touted by Bushveld and AfriTin are either low-grade or low-tonnage, and so will not make a significant impact on the market. Even the infamous potential of Alphamin’s Mpama North will not be sufficient to negatively impact the commodity price (Mpama South may change this, see below).

A bull market such as this will of course result in a correction at some point, but as London-based tin expert Mark Thompson recently disclosed in an interview, we need to see multiple new hard-rock mines come online over the next couple of decades to fill looming supply gaps. Thompson goes on to say he believes we need $35,000 for at least a two years before the banks and the mining funds will lend to new producers, but in the interim he’s expecting to see $50,000 in cash in the next six to 12 months.

Potential for existing suppliers to scale

While this leaves ample room for existing producers to expand, Alphamin simply can’t grow fast enough – the area is rumoured to have once produced around 10% of global tin supply through artisanal mining of scree slopes containing cassiterite along the Mpama ridge and some tunnels into the ore body. However, since industrialisation aims to produce a saleable concentrate rather than raw ore, output at Mpama North currently stands at around 4% of global supply.

It is highly likely that Mpama will be able to reach and exceed 10% once more. The area was mined by local artisanal miners for long enough that, while not NI 43-101 compliant, those in the know locally have an extreme degree of confidence in the site’s ability to scale. Exploration of an area known as Mpama South, just 750m away from the current operation, has yielded exploration results just as impressive, and Alphamin has readily engaged in the expansion of the current separation plant in preparation for increased throughput.

The beneficiaries

As previously mentioned, Bushveld and AfriTin tout two tin projects, one in Namibia and one in South Africa. The Namibian project has good overall tonnage at 71.54 million tonnes, but the grade of 0.134% Sn leaves a lot to be desired. Similarly, the South African project has a current estimated potential production of around 700 tonnes per year, which is hardly expected to be market moving.

Mpama North generally comes out at around 4% tin, and the company has even had to work with miners to reduce the average feedstock grade to allow effective concentration by gravity separation. The site has a current measured, indicated and inferred resource of just under 5 million tonnes at 4.6% Sn and a mine life of 12 years.

This looks set to change, however: 2021 exploration efforts at Alphamin’s Mpama South have revealed grades of up to 10% tin in run of mine (ROM) ore. Alphamin’s current exploration initiative aims to extend the life-of-mine, declare a maiden mineral resource for the Mpama South Prospect, and discover at least one additional deposit along 13km of strike at the highly prospective Bisie Ridge.

Summary

The tin price has considerable support from the backed-up electronics and automotive industries and a lack of new economical resources. Explorers will certainly benefit from increased financing in the short-term, but this is not expected to weigh on prices for a number of years.

In the interim, the scope for new producers to come into the market is considerable. Sustained high prices will ultimately lead to brownfield expansions from lower grade high cost resources-but is this enough? If tin demand grows at 4-5% per year for the next five years, that means that we need almost 100,000 tonnes more tin per year. That’s ten Alphamins!

As it stands, Alphamin has the highest grade tin operation in the world, is a scalable project that is already in production and growing output. Its cost base of $10,000/tonne leaves the company with a healthy cash margin of over $25,000/tonne at current prices. If tin prices hit $50,000/tonne, Alphamin’s cash margin will double making it a pretty robust investment.

Comparables

Bushveld Minerals Ltd (LON:BMN)

Bushveld Minerals owns 17.48% of AfriTin Mining, and represents a limited exposure to the tin market. The company is well-established and secure, with a primary focus on vanadium.

AfriTin Mining Ltd (LON:ATM)

A spin-off of Bushveld Minerals, AfriTin Mining is currently developing two tin projects in southern Africa. The company expects production costs in the lowest quartile from one past-producing mine and one new discovery.

Alphamin Resources Corp (TSXV:AFM)

Alphamin owns a 95% stake in the historic Mpama Ridge tin deposit. Contributing 3% of global tin supply and known as the highest-grade tin mine ever discovered, the project is on the verge of significant expansion.

To learn more about Alphamin Resources, click the image below.